I wrote a tribute to this beautiful object for the April 2011 issue of PRINT magazine in the regular column "One Perfect Thing."

Here is my story in total:

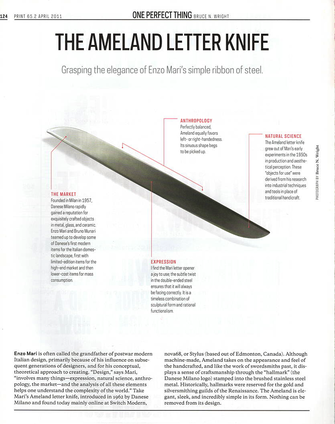

Enzo Mari is often called the grandfather of postwar modern Italian design, primarily because of his influence on subsequent generations of designers, and for his conceptual, theoretical approach to creating. “Design,” says Mari, “involves many things — expression, natural science, anthropology, the market — and the analysis of all these elements helps one understand the complexity of the world.” Take Mari’s Ameland letter knife, introduced in 1962 by Danese Milano and found today mainly online at Switch Modern, nova68, or Stylus (based in Edmonton, Canada.) Although machine-made, Ameland takes on the appearance and feel of the handcrafted, and like the work of swordsmiths past, it displays a sense of craftsmanship through the “hallmark” (the Danese Milano logo) stamped into the brushed stainless steel metal. Historically, hallmarks were reserved for the gold and silversmithing guilds of the Renaissance. The Ameland is elegant, sleek, and incredibly simple in its form. Nothing can be removed from its design.

THE MARKET

Founded in Milan in 1957, Danese Milano rapidly gained a reputation for exquisitely crafted objects in metal, glass, and ceramic. Enzo Mari and Bruno Munari teamed up to develop some of Danese’s first modern items for the Italian domestic landscape, first with limited-edition items for the high-end market and then lower-cost items for mass consumption.

ANTHROPOLOGY

Perfectly balanced, Ameland equally favors left- or right-handedness. Its sinuous shape begs to be picked up.

EXPRESSION

I find the Mari letter opener a joy to use, the subtle twist in the double-ended steel ensures that it will always be facing correctly. It is a timeless combination of sculptural form and rational functionalism.

NATURAL SCIENCE

The Ameland letter knife grew out of Mari’s early experiments in the 1950s in production and aesthetical perception. These “objects for use” were derived from his research into industrial techniques and tools in place of traditional handicraft.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed